Patient of the Month- Stephen A.

If you would like to donate to Soft Bones in honor of Stephen, please click the button below!

Walking the Walk: My Journey with Hypophosphatasia

When I was 14 years old, I began a journey that would eventually span decades, multiple diagnoses, 27 orthopedic surgeries, and a search for answers.

I had my first of several distal femoral lesions appear in both of my knees, confined solely to the lateral aspects. At the time, I was diagnosed with osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), with no evaluation for metabolic (endocrine) bone disorders. Between 1998 and 2002, I had a total of four surgeries on my left knee and two on my right knee. As the lesions dislodged, a series of microfracture and debridement procedures were conducted with some success. In 2001, a very large lesion dislodged from the lateral condyle in my left femur. This required an extensive osteoarticular transplant (OATS) procedure to “plug” the vacated condyle and underlying bone.

Fig. 1. My high school basketball team (senior year), with me in a common position: on crutches in the top left! I was able to play my sophomore and part of my junior year, but my career thencame to an end due to HPP, which we did not know at the time.

From 2003 through 2009, my orthopedic issues disappeared. I was an avid weightlifter and exercised religiously. However, by 2010, familiar symptoms began to recur in my left knee, at the very location of the OATS graft. Another microfracture was attempted by my surgeon. It ultimately failed.

Around this time, my father pointed out that my left knee was significantly valgus (“knock-kneed”). It turned out my knees were turned inwards about 13-14 degrees, which prompted referral to one of the knee surgeons in Omaha who did “big” procedures. He recommended a distal femoral osteotomy (DFO), a procedure to eliminate most of the valgus and hyperextension in that knee to unload the OATS graft. I got this procedure done in 2011.

By all accounts, it was very successful, but 6 months post-op, much of the osteotomy site had yet to heal to my surgeon’s satisfaction, which led him to inquire about potential metabolic abnormalities in the execution of my osteoblast/osteoclast (i.e., bone

formation/metabolic) processes. It did not heal until we used a non-invasive bone healing treatment.

From 2010 onward (when electronic medical records became available in Nebraska), I noticed I had consistently low values of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) whenever I was tested. My PCP, at the same time, brushed it off. However, the same knee surgeon who performed my DFO immediately referred me to Creighton University Medical Center (CUMC) endocrinology. In 2013-2014, biochemical assays and eventual CLIA-certified genetic testing confirmed juvenile-onset (now more commonly referred to as “childhood”) hypophosphatasia (HPP). I was formally diagnosed by Dr. Rush at Nebraska Medicine.

Furthermore, in 2013, I had an iliac crest biopsy conducted, which revealed no trabecular remodeling in the bone specimen and minimal cortical remodeling, hallmarks of adynamic bone disease (ABD). I had HPP comorbid with ABD, a combination that had never before been documented.

Fig. 2. Me and my service dog Cosmo following a hospital stay.

I began Strensiq in 2015. I was on it for two years and then stopped. I tried it again in 2019 for one month. Both times, I did not respond to Strensiq. The consensus (amongst others beyond Dr. Rush) is that I did respond from 2015-2016, but my clinical symptoms returned in 2016. My average and maximum ALP dropped significantly in 2016-2017, my kidney function declined when it had previously shown marked improvement, and my biomarkers of bone turnover never really increased. While I was never formally tested for neutralizing antibodies, it remains the consensus for my lack of response, and also the neurological symptoms I quickly developed when trying treatment again in 2019.

This has not stopped me from promoting Strensiq as a life-changing, life-saving treatment for the majority of HPP patients who benefit from it.

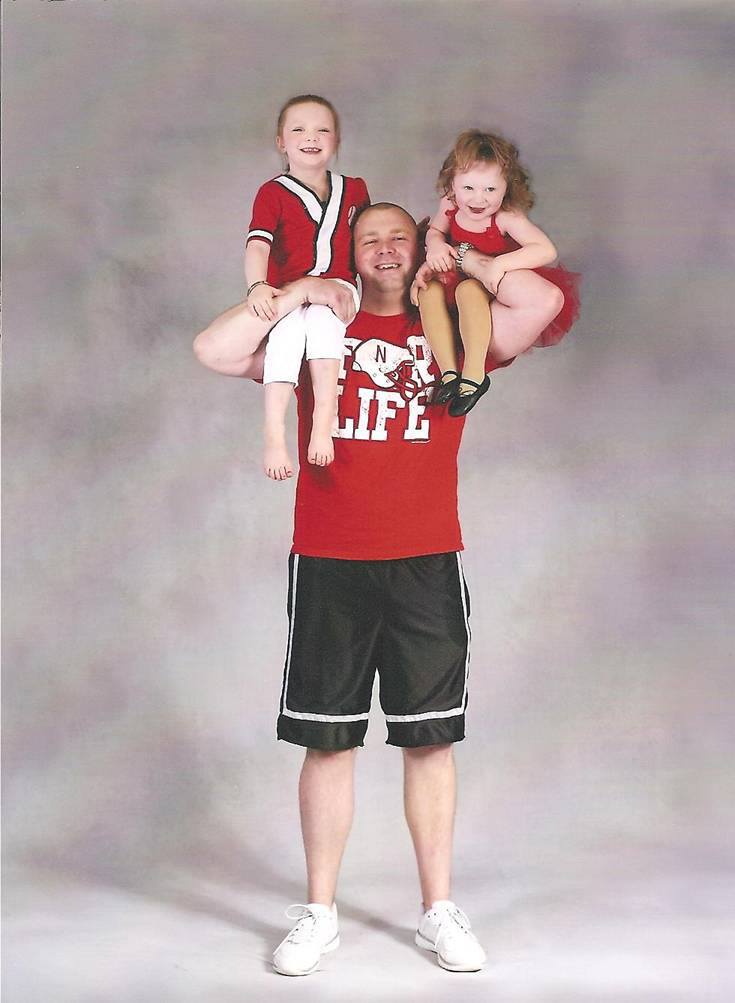

Fig. 3. Me before I was sick.

Living with HPP has meant facing not only physical pain, but also emotional and mental challenges. The mental side of the disease (for me) is profoundly more difficult than the physical side. Yes, I have had 27 orthopedic surgeries directly attributable to HPP, but that pales in comparison to the hours I have lost worrying due to anxiety and depression, or feeling regret for not being able to do so many things with my family. It’s hard not to let the disease define who you are, because it impacts everything. The physical, the mental, the emotional, and yes, even the spiritual. Currently, I am dealing with four primary rare diseases (HPP, Addison’s disease, Panhypopituitarism, and Sjögren’s syndrome), six if you count those that have developed comorbid with the four.

Despite it all, I’m proud of what I’ve overcome. I started working for the Department of Defense (DoD) in 2005 as an intern, was diagnosed with HPP in 2014, and continued to work another seven years in a mentally demanding role. When I filed for disability, the Administrative Law Judge in my SSDI disability case actually pointed out in his ruling how long I was able to keep working despite so many crippling diagnoses.

I have been able to help so many more people with their struggles, those with and without HPP, than I would have otherwise because I have and continue to “walk the walk”.

— Stephen A.

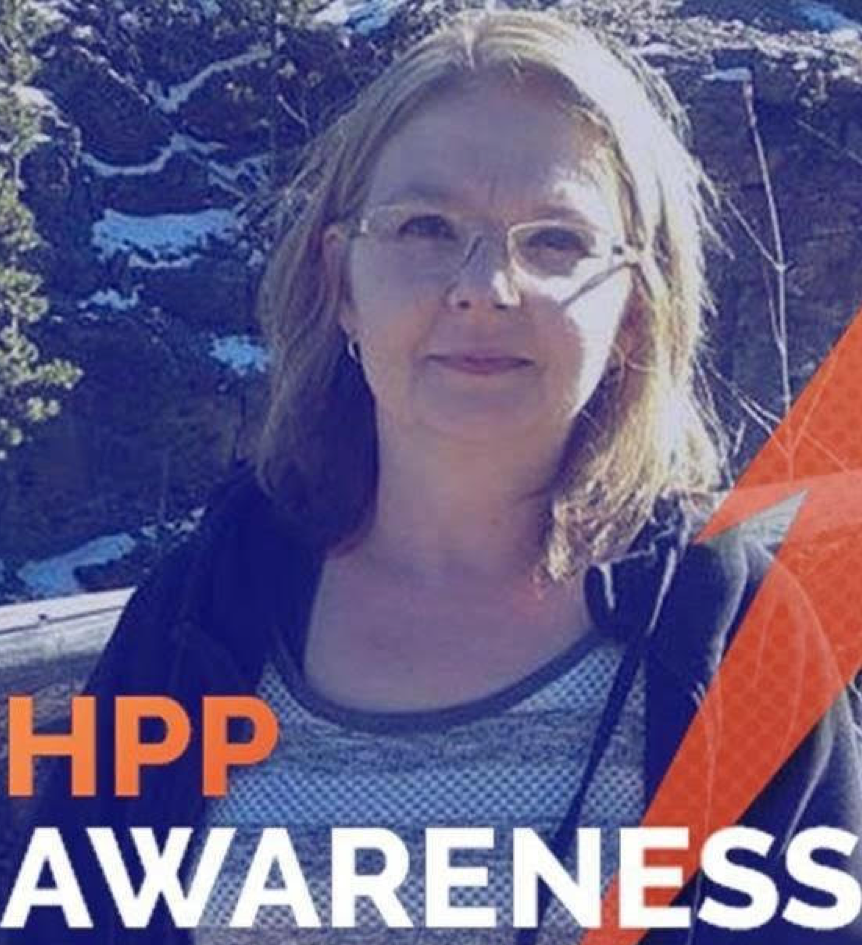

Fig. 4. Most of the Nebraska HPP kiddos, me, and Dr. Eric Rush at the 2017 US Soft Bones Foundational National Meeting in Kansas City.

Soft Bones has been an enormous and positive part of my life. It’s a conduit through which I can help people, and that makes me proud, while also helping me cope with my struggles. There are few things more therapeutic than helping others.

While this disease is extraordinarily difficult and I would not wish it upon anyone, I do feel that I am a stronger, more empathetic person because of it. Having watched me go through it, my two teenage daughters are stronger and more empathetic ladies.

I have been able to help so many more people with their struggles, those with and without HPP, than I would have otherwise because I have and continue to “walk the walk”. Lastly, my scientific understanding allows me to simplify complex concepts so it is easier for others to understand and discuss with their physicians.

While I am not a formal Soft Bones employee, I feel like I am a very valuable contributor to the organization, especially in the scientific scope. I am someone that others can turn to for informal help or assistance, someone Soft Bones can occasionally lean on for informal scientific support, and someone who is very well connected with his physicians and can quickly get answers to complex problems.

Fig. 5. Me and Cosmo at the hospital.

What I want the world to know about HPP is this: it may be the most variable inborn error of metabolism ever discovered. However, through the unifying efforts of the Soft Bones, it has also been at the forefront of ongoing, groundbreaking research in both enzyme replacement and gene therapy. That’s what happens when a patient population that is well-organized under one umbrella (Soft Bones) makes them a target for research opportunities. I don’t think anyone with HPP would be in the position they are in without Soft Bones. Would Strensiq have been approved in 2015? Would ALXN1850 (new medication being studied for the treatment of HPP) be on the precipice of approval? Would the foray into gene therapy for HPP be so advanced? Where would we turn to in our times of need?

The answer to all of those questions is probably no. Soft Bones is a life-changing, possibly life-saving organization that one physician has described to me as the most well-organized rare disease support organization he has ever seen.

Fig. 5. Manuscript published on my erroneous biochemical assays while on Strensiq, which largely launched the foray into Strensiq lab interference and FDA label update. Click HERE for full article.

Responses